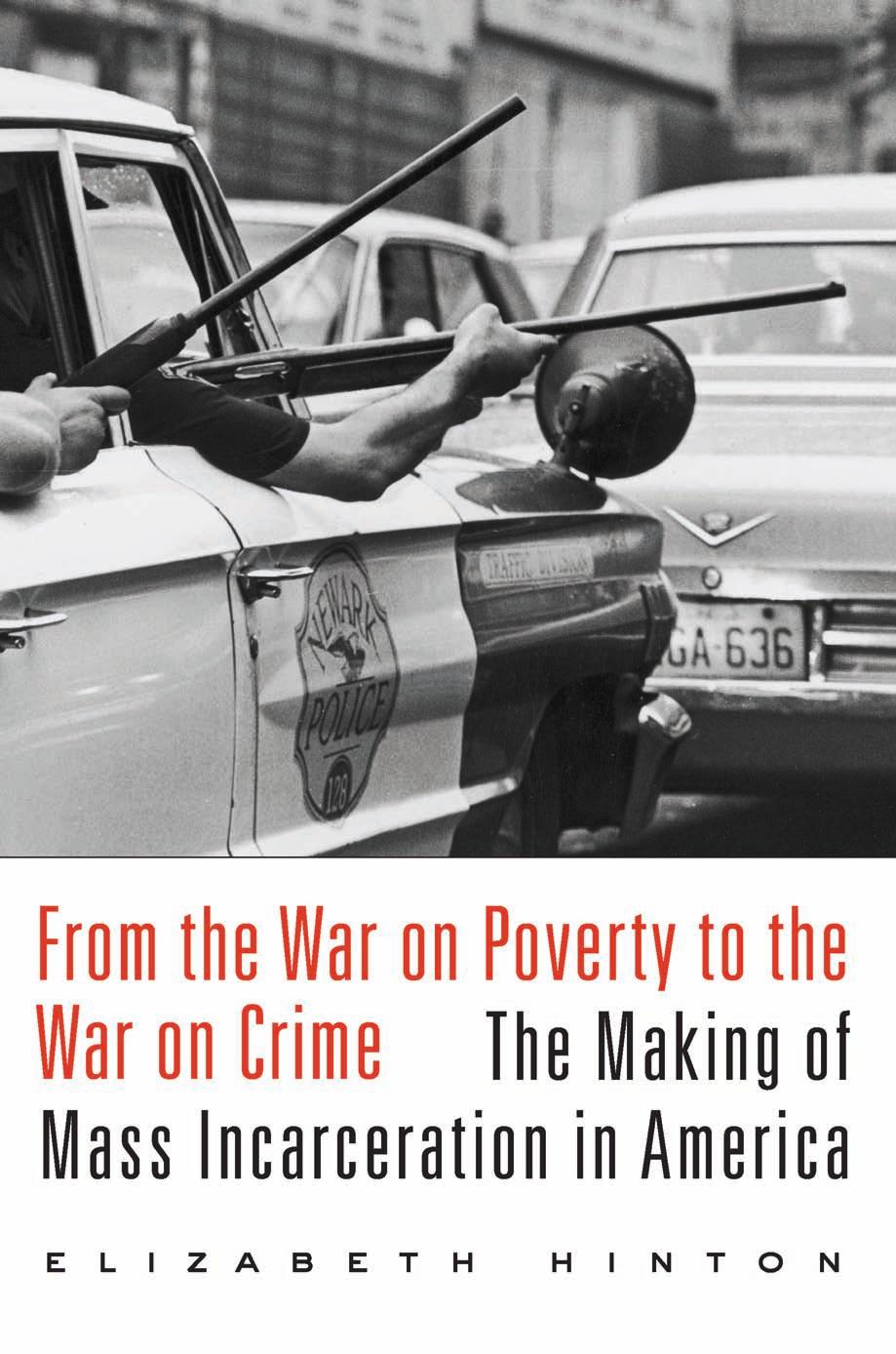

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America by Elizabeth Hinton

Author:Elizabeth Hinton [Hinton, Elizabeth]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 9780674737235

Publisher: Harvard University Press

Published: 2016-05-08T22:00:00+00:00

PUNISHING “POTENTIAL CRIMINALS” AND “DELINQUENTS”

As the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act successfully removed white youth from penal institutions and provided them with rehabilitative services, it vastly expanded the reach and resources of urban police in nearly every facet of the lives of black youth. With private and community-based organizations handling “less seriously delinquent youth,” federal policymakers relied more than ever on the law enforcement community to deal with the groups of delinquents and potential delinquents who they felt posed a more serious threat to public safety. This shift had its roots in the mid-1960s, when punitive programs first became a major component of domestic social policy. Thereafter, police received increasing proportions of federal funds and had come to assume many of the responsibilities that had previously been entrusted to social welfare authorities. By the mid-1970s, federal disinvestment from the public sector and the remnants of War on Poverty programs meant social welfare agencies in urban centers had little choice but to incorporate crime control measures in their basic programming in order to receive funding.34

The 1974 legislation opened up new avenues of inclusion for law enforcement authorities in the everyday operation of a range of public institutions—but none more so than urban schools. The federal government approached the problem of school violence as it had other crime war battles: through planning, patrol, and hardware. In establishing the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Congress gave the Justice Department new power within public school systems. Simultaneously, when it renewed the Secondary Education Act in the summer of 1974, it introduced widespread police patrol in the hallways and classrooms of schools serving “economically and educationally disadvantaged children.” Less than a year after the passage of these punitive programs, officials in the Ford administration in the spring of 1975 proposed various “target hardening” techniques to further increase surveillance and patrol of low-income students by combining electronic surveillance, improved security of school buildings, and an increasing presence of law enforcement officials on the campuses of urban public schools. While some Ford staffers recognized that the approach “may contribute to a feeling that the school is really under siege,” the president and Congress pressed on for implementation.35 The doubters were right, however, and none of these strategies effectively controlled youth crime as policymakers and law enforcement officials had intended.

School security forces and similar surveillance techniques had been established in a number of urban public schools in the context of urban uprisings during the second half of the 1960s. Yet what started as closed-circuit televisions and groups of city police officers roaming the halls evolved into school police forces in their own right by the mid-1970s as federal policymakers and local law enforcement authorities escalated the war on youth crime. At Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles, for example, four police units patrolled the perimeter of the school grounds while a helicopter flew overhead on the hour. Three armed guards stood at the entrance of the school, which was cordoned off by a steel metal fence with padlocked gates.

Download

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America by Elizabeth Hinton.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19027)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12182)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8883)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6872)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6260)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5782)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5734)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5491)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5423)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5211)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5139)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5078)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4946)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4911)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4775)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4738)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4696)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4500)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4481)